Software driven platforms have come to increasingly rule our lives and now we have the flying horse, not from Greek mythology, but AI-enhanced cryptographic software Pegasus from Israel. It truly is a season of flying horses, start-ups and IPOs.

Points to Ponder. Initial Public Offers (IPOs)

- September 11, 2021

- Posted by: Arunanjali Securities

- Category: Business

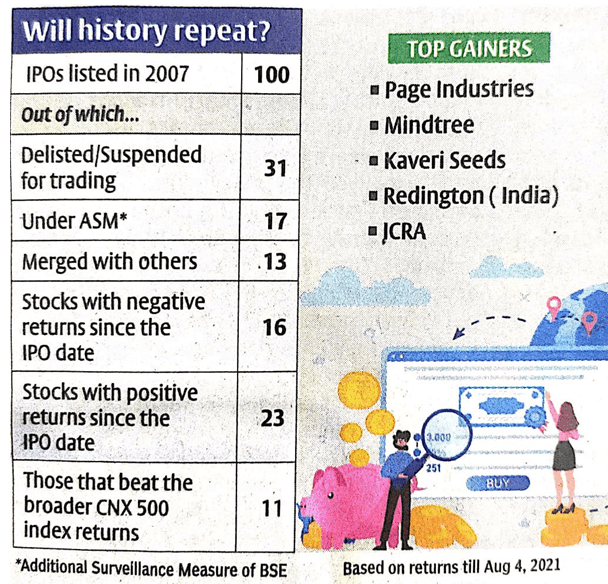

IPOs are essential to provide fresh,high powered capital that drives investments and provides depth and diversity to the secondary capital market. The current spate of IPOs, however, is more by way of offer for sale than for financing fresh investments or expansion of existing activities.While offer for sale at attractive valuations does offer profitable exit to venture capitalists and PE investors, thereby supporting the startup ecosystem, they come at great risk to IPO subscribers, particularly, the retail subscribers. With promoters, generally tapping the primary capital market during bull phases with astronomical valuations, subscribers get little from IPOs except the ephemeral listing gains fueled mainly by the liquidity backedeuphoric rush for such issues.Eight months into 2021, about 27 IPOs have hit the market with a total issue size of close to Rs 40,000 crores and many more are in the pipeline with most issues seeing record oversubscriptions. With startups testing the capital markets, the refrain (as in the past) is, “it is different this time”. But is it really? Data from PRIME database showthat out of 100 IPOs that listed in the IPO frenzy of 2007, only 23 stocks delivered positive returns (till date). In fact, only one in about 10 shares has delivered returns beating the broader market CNX 500 index during the period up to now. The tablebelow succinctly tells the story.

There were, of course, a few companies that have stood out.Page Industries is the top performer from the 2007 IPO list, having gone up from an offer price of Rs 360 to Rs 32,760, a return of nearly 100 times! The next in line are Mindtree and Kaveri Seeds with a price rise of 30 and 20 times, respectively. Redington and ICRA also gave a handsome 10 fold returns over their offer price.

But one swallow doesn’t make a summer. Moreover, past winners may not provide a clue to future winners. To complicate matters further the next gen companies come with a whole new set of business models. For instance, technology driven startups call for different valuation metrics, as unlike conventional businesses they come to the market with losses and with only a promise of profits in the future. After Zomato, public issues of Mobikwik, Paytm, Nykaa, Policybazaar, Ixigo, Delhivery, Flipkart etc., are said to be in the pipeline. Here the offer documents are replete with terms like GMV, AOV, cash burn, MAU, DAU, CAC, churn etc. These concepts essentially focus on operational metrics in the absence of profits. Thus GMV or Gross Merchandise Value denotes total transaction volume of merchandise through the “market place”in a specific period.

In the case of Paytm,FY 21 GMV is Rs 4 lac crores. But actual revenues could be only a portion of the GMV. Revenue consists of various fees charged by the company. For instance, for Paytm the revenue from operations is Rs 2800 crores, less than 1 per cent of GMV. Another important metric for IPO bound startup is cash burn. It is computed by subtracting cash balance at the beginning of the year from the cash balance at the end of the year. When Google was burning cash in 1999-2001, money was going into building high tech internet products. Hence it is crucial for investors to identify whether the fund raise is aimed to just meet expenses or, to fund growth.To understand positive unit economics one has to analyse Average Order Value (AOV) which is derived by dividing GMV by the number of orders in a specified period. If the AOV covers the cost per order, one can project the volume required for the company to break even.

Similarly, depending on the nature of a company’s business, there could be other measures to assess the performance and or potential of the company. Some companies find it useful to count Monthly Active Users (MAU) or Daily Active Users (DAU). Facebook, for instance, defines a daily active user as a registered and logged-in Facebook user who visited Facebook through its website or a mobile device, or used Messenger application, on a given day. Twitter uses Monetisable Daily Active Users (mDAU) as those who logged in or were otherwise authenticated and accessed Twitter on any givenday through twitter.com or Twitter applications that are able to show ads.

The very least aninvestor in an IPO could do is to monitor the anchor investors for the IPO. These are institutional investors who are offered shares a day before the IPO opens. Typically, they are mutual funds, insurance companies and foreign funds. They ‘anchor’ the issue by agreeing to subscribe for the shares at a price within IPO price band. Unlike brokerages who just put out IPO reports, anchor investors have skin in the game. Hence if the issue has any problems, their response could be tepid. There have been instances of some issues failing to mop up money from anchor investors or anchor investors bidding at lower end of the price band. Since anchor investors cannot sell the shares allotted to them for at least 30 days from the date of allotment of shares, they need to be doubly careful when they invest as anchors. Anchor investor details are published in BSE Notices and NSE Circulars a day before the IPO opens for the public. These communiques mention shares allotted to each anchor, percentage of anchor allotted portion, value of shares allotted and so on.

The bottom line: If caveat emptorare the watch words for the investor, then there is no substitute for homework.