Aspects of Ageing and Economic Consequences

- July 20, 2025

- Posted by: Arunanjali Securities

- Category: Business

Economic consequences of an ageing population are fairly well documented. A significant cost on the economy of an ageing population is due to shrinking workforce and increasing healthcare costs. This can lead to slower economic growth, reduced productivity and challenges for public finance. Change in age structure can affect labour markets, saving and consumption and social security systems. The increase in healthcare and pension costs, coupled with lower savings rate and reduced investment could significantly impede GDP growth.

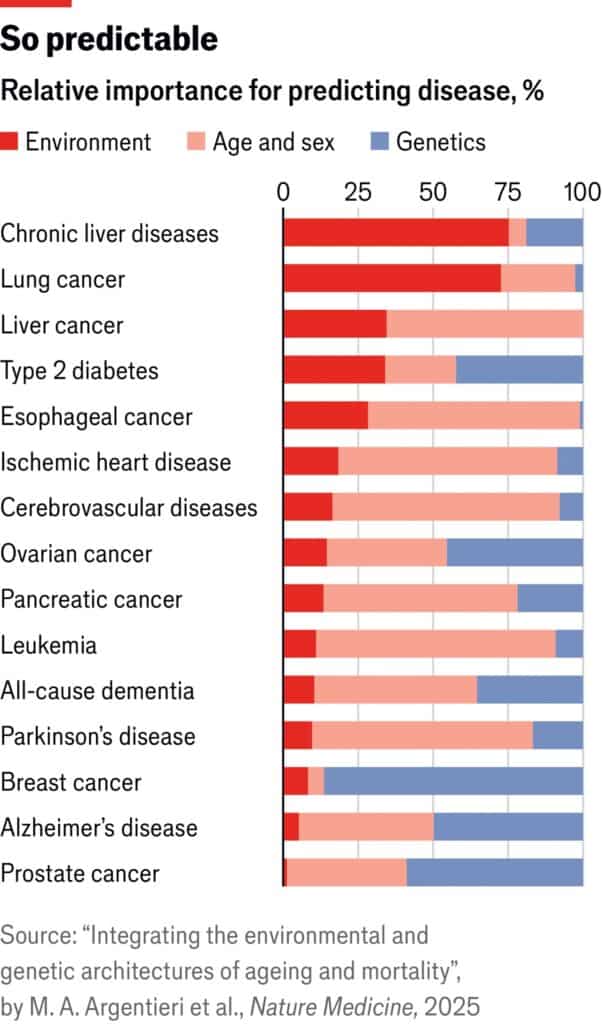

Yet today Silicon Valley billionaires pour fortunes into cutting edge longevity treatments. But a recent study published in Nature Medicine which draws on the UK biomedical data base, seems to suggest that the real secrets to a longer life are neither mystical nor high-tech. The study suggests that genetics play a surprisingly minor role in overall longevity. While age and sex (47%), environment and lifestyle (17%) explain over 60% of the variability in mortality, genetics added a mere 3%. The study could not identify factors to explain remaining variability in mortality. Chart 1 below identifies environmental and lifestyle factors with strongest influence on mortality. While expectedly, smoking increases the risk of premature death, social connections were surprisingly powerful predictor of a long life. Physical activity reduced the risk of mortality by roughly 25%. But guess what;

living with a partner was roughly as beneficial as exercise. Loneliness, it was found also affects mental wellbeing – another factor in longevity.

So, a workforce that is healthier for longer could be part of the solution in containing the adverse effects of ageing on the economy. This would make other mitigating strategies such as postponing retirement age, continuing skill enhancement even for employees who enter their 50s and 60s, increased adoption of technology and encouraging innovation to enhance the productivity of senior workforce, etc., more effective.

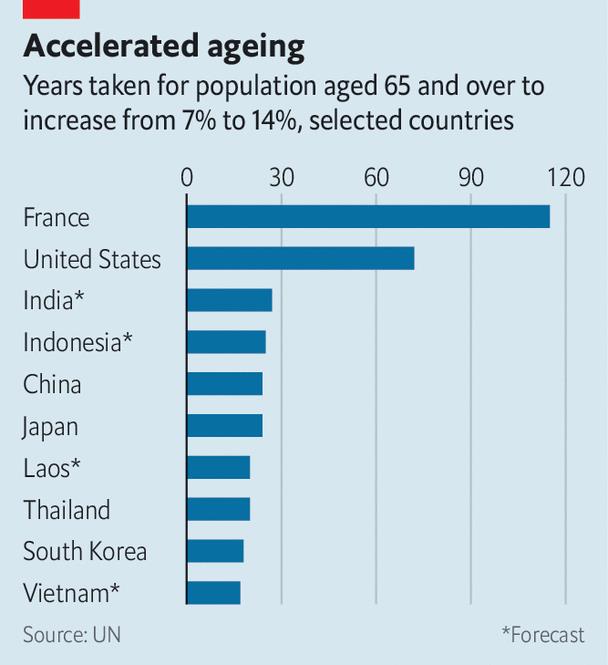

But as the Economist observes large parts of Asia are getting old before they get rich and it means that even poor countries must start planning for an ageing population.

A bulge in a country’s working-age population is a blessing. Lots of workers support relatively few children and retired people. So, as long as the labour market can absorb a surge of job-seekers, output per head will rise. That can boost savings and investment, leading to higher economic growth, more productivity gains and developmental lift-off. Yet for countries that fail to seize this opportunity, the results can be grim—as many developing countries may soon discover.

Consider Thailand. It is rapidly greying. In 2021 the share of Thais aged 65 or over hit 14%, a threshold that is often used to define an aged society. Soon Thailand will, like Japan, South Korea and most Western countries, see a dwindling supply of workers and, without extraordinary measures, flagging productivity and growth. Yet unlike Japan and the rest, Thailand, with a GDP per person of just $7,000 in 2021, is not a developed country. It has got old before it has got rich. When Japan had a similar portion of oldies, it was roughly five times richer than Thailand is today.

This is a big obstacle to Thailand’s future development. To protect its ageing citizens, many of whom are poor, Thailand’s government will have to spend more on health care and pensions. This will make it harder to invest in productivity-boosting skills and infrastructure. And where Thailand goes, many developing countries will follow. In Asia, where the problem is most advanced, Indonesia and the Philippines are also likely to become aged societies at lower

income levels than was the case in the rich world. Sri Lanka, where the average income is a third lower than Thailand’s, will become aged by 2028.

The above prognosis would suggest that countries with a working-age bulge need to wring more growth out of it. India may never have a better chance than the present. Under the prevailing stable, pro-business government, there is a consensus on the measures, including privatisation and looser foreign-investment rules, that could raise its growth rate. Such reforms would help India take advantage of Western efforts to shift supply chains out of China. If India needs a cautionary tale to justify action, it need look no further than its own rapidly ageing southern states. In Kerala 17% of the population is 60 or older.

Another conclusion is that developing countries need to start planning for old age earlier. They should reform their pension systems, including by raising retirement ages. They should nurture financial markets, providing options for long-term saving and health insurance. They should create conditions for well-regulated private social care. And they should try harder to increase female participation in the labour force; in India it is a wretched 24%, half the global average. Getting more women into jobs would extend the demographic dividend and help deal with the fact that women live longer than men, but tend to have more meagre savings and pensions, and so are vulnerable in old age.

Finally, developing countries should learn from the errors of rich ones by taking a pragmatic view of immigration. Hard as this can be politically, it is often the easiest way to extend the

transition. Building sites in Bangkok already throng with illegal Burmese immigrants. By formalising them, Thai politicians could usher them into more productive roles.

Here, India provides a happier example of this. A continent-size country, its boom is fuelled by internal migration. Its last census, in 2011, counted 450m internal migrants. Many travel from the poor north to the more prosperous south and west, to seize new opportunities and, increasingly, to take up those being vacated by the south’s ageing workers. It is an inspiring illustration of what relatively unfettered labour markets can do—and a lesson for Japan, Thailand and governments everywhere.