What Ails World’s Fastest Growing Large Economy?

- October 15, 2024

- Posted by: Arunanjali Securities

- Category: Business

Indian economy, it appears, is firing on all cylinders. The bond and equity markets are rocking with both domestic and global funds chasing Indian assets. IPOs keep hitting the primary market at a scorching pace and the accelerating credit off-take pushing banks to flirt with a credit deposit ratio of 80%. The buoyancy in tax collections, both direct and indirect, has helped the government reduce fiscal deficit over successive budgets. No less a person than the RBI Governor speaks of improved fundamentals with fiscal consolidation, healthy bank balance sheets, a declining inflation trajectory and comfortable level of foreign exchange reserves, helping the country to navigate through supply side disruptions due to geopolitical disturbances and geoeconomic fragmentation. The IMF, IBRD (World Bank), ADB, OECD, as well as major rating agencies agree that India will remain the fastest growing large economy registering a GDP growth of about 7% even in 2024-25.

It could be perilous to be a Cassandra in milieu of pervasive euphoria! Nevertheless, it is precisely in such a situation that one has to look for chinks in the armour, lest complacency make the system heedless of the lurking risks. In size, India is the fifth largest economy with a GDP in 2023 estimated at $ 3.55 trillion. But our per capita income is only $ 2484. This certainly is an improvement when compared to corresponding income of $1440 a decade ago. But it is still abysmally low when compared to the per capita income of $12514 of China. Others like Australia, Japan and South Korea boast of a per capita income of anywhere between $33000 to 65000. Even countries like Egypt, Sri Lanka and Vietnam rank above us. So, is it only population, or is there any other reason that India finds itself at the 137th spot in a list of 192 countries listed according to their income? A comparison with China would suggest that population alone does not explain this poor performance.

Part of the explanation has to be found in the low productivity of the agriculture sector. As the Economist puts it, “India has come a long way since “ship-to-mouth” days of the 1950s and 1960s, when the country depended on food aid from abroad. It has long since become a net exporter of stuff people eat. Yet big inefficiencies persist. Although India has a third more land under cultivation than China, it harvests only a third as much produce by value, according to analysis by Unupom Kausik of Olam, an agri-business listed in Singapore. Agriculture employs almost half of all Indian workers—some 260m people—but contributes only 15% of output and 12% of exports (see chart above). By contrast, business services such as call centres and IT companies employ less than 1% of workers but produce 7% of GDP and almost a quarter of exports”. So the major challenge in raising the per capita income in India lies in tackling the vicious cycle of low productivity and pervasive invisible unemployment and underemployment in the agriculture sector.

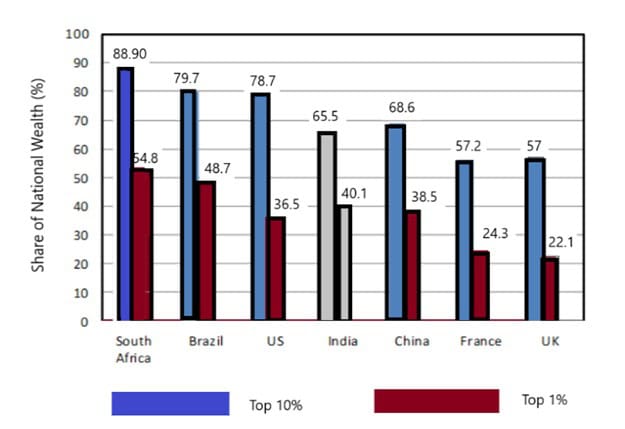

Another disturbing feature of the Indian economy is the increasing inequality in the wealth and income distribution. The research group, World Inequality Lab says that the wealth concentrated in the richest 1% of India’s population is at its highest in six decades and this percentage share of weaith exceeds that of many countries including US, UK and France. (see chart below).

The study which was authored among others by the redoubtable Thomas Piketty, found that by the end of 2023, India’s richest citizens owned 40.1% of the country’s wealth, the highest since 1961 and their share of the total income was 22.6%, the most since 1922.

The Lab says that factors, including lack of quality education has trapped a substantial swathe of people in low paid jobs and depressed the growth of the bottom 50% and middle 40% of the Indians. Data from Forbes billionaire rankings show the number of Indians with net wealth exceeding $ 1 billion rose from 1 in 1991 to 162 in 2022. The 10000 wealthiest individuals own an average of Rs 22.6 billion ($ 271.91 million) in wealth, which is 16763 times the country’s average. The top 1% own over 40% of the county’s wealth. Since India, which won its independence in 1947 from Britain, opened its markets to foreign investments in 1992, the number of billionaires has surged. The authors of the study observe that the “Billionaire Raj” headed by India’s modern bourgeoisie is now more unequal than the British Raj headed by colonial forces.

The final question that cries out for an answer is: Are Indians happy? The UN sponsored World Happiness Report ranks India near the bottom at 126 out of 143 countries surveyed. It appears that countries with relatively smaller population rank among the top “happiest” countries. Only Canada and the UK have populations of over 30 million among the top 20 happiest countries. While the US and Germany have gone out of the top 20, being ranked 23rd and 24th, Costa Rica and Kuwait entered the top 20 group, ranked at 12 and 13. Finland continues to be the world’s happiest country.

The happiness ranking is based on individuals’ self assessed evaluations of life satisfaction as well as per capita income, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom, generosity and prevailing corruption levels.

Jennifer De Paola, a happiness researcher at the University of Helsinki in Finland, says that Finns’ connection to nature and healthy work life balance are contributors to their life satisfaction. May be it is time that we Indians have to take time off to introspect whether blind pursuit of progress as represented by “improving macros” is the route to happiness or a life style that is in harmony with nature and neighbour?