Whither Fossil Fuels?

- September 24, 2022

- Posted by: Arunanjali Securities

- Category: Business

A big question mark hangs over the prospects for fossil fuel industry given its adverse environmental impact. Consider the following:

EV adoption is accelerating, solar panels are getting cheaper (at a faster rate than the most optimistic estimate), battery cost has decreased by 89% from 2010 to 2021 and renewable energy’s contribution to the global grid is increasing (China alone will add 140 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity, more than rest of the world combined in 2020. It is also planning on building 150 new nuclear reactors, more than rest of the world has built in the past 35 years.) To make matters worse, fossil fuel industry is in a political crosshair, especially with energy cost fueling much of the global inflation. Two of the industry’s largest companies, Shell and Exxon, recognized in the 1980s that their products contributed to the warming of the planet, which would lead to global catastrophes and political instabilities. Decades later, they were proven right. To mitigate the reputational damage, in recent years, Shell and other oil companies have taken a more public stance in recognizing the impact of fossil fuels towards climate change. Despite this, behind closed doors, they also participated in lobbying efforts that oppose climate policy and promote climate skepticism.

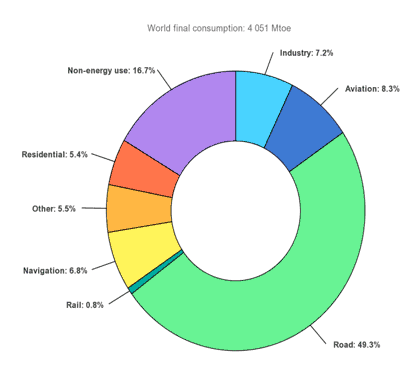

Will oil ever go to zero? The following figure might provide some clues while attempting an answer to the question.

Figure 1: World’s oil consumption by sector. Source:IEA

Transportation sector is the biggest consumer of oil. But even with the advent of EVs, it will take decades to completely eliminate this consumption. The glide path to a complete replacement of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles with EVs is projected to take decades. Bloomberg estimates that there will still be 900 million ICE vehicles on the road in 2040 – more than half the existing fleet. Oil consumption from transportation will decline, but will not reach zero. Outside transportation, demand for plastics (which are made of oil) is supposed to surge and help drive growth of consumption. Petrochemicals account for about 14% of oil use and in the past decade large producers have invested more than $200 billion in plastic and chemical projects in the US. Some argue that this investment won’t pan out. Plastics are a much smaller revenue contributor and face concerted legislative efforts to curb its use.

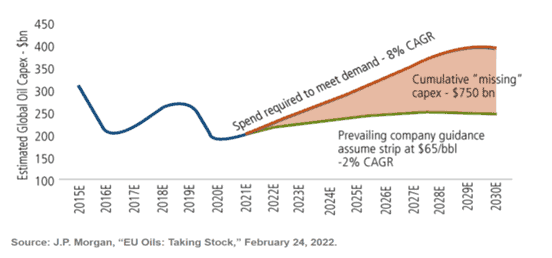

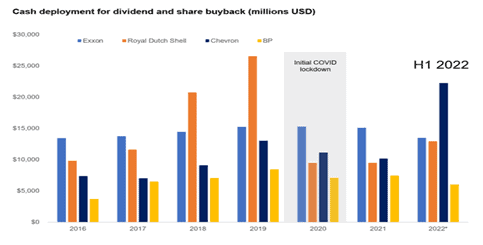

All this means that while in the long term, the sector is despised, with middling demand growth, in the short term, demand is expected to increase, outpacing supply giving rise to a new found fiscal discipline in the industry. Capital expenditure (capex) of producers went down in 2020, the year the world went into lockdown, and has not recovered since.

Figure 2: Gap in needed Capex vs. current investment projections by 2030

(Material drawn from Vested, Morgan Stanley and International Energy Agency)