The citizen who by now is inured to the hype every budget comes with, might as well say, a la Tennyson’s Brook, budgets may come, budgets may go, but the economy goes on!

In fact, the question is why all this hullaballoo about budgets, when Finance Ministers routinely announce major decisions such as the path breaking drastic reduction in corporate tax or the National Infrastructure Pipeline with an outlay of 102 lac crores spread over five years, or the alternative investment fund with a corpus of Rs 25000 crores for last mile delivery of stalled housing projects, outside the budget? Even when it comes to major source of revenue, namely, indirect taxes, the GST regime which subsumes most of them, is the domain of the GST council where Finance Minister is only a first among equals and the budget has little to do with it.

But budget is a constitutional necessity. This apart, it is an opportunity for stock taking, to assess the achievements or failures vis-a-vis the budgets estimates for the year gone by and for chalking out a plan to realize the aspirations and objectives for the coming year . But more importantly it sets out a plan for harnessing resources and funds to achieve the budget plan. The tax proposals, the expenditure outlays and deficit spending, have wide ranging implications for the economy as a whole, affecting bond, stock and commodity markets as also money and exchange markets and even impacting the monetary policy of the central Bank.

The budget aggregates, particularly the quality of expenditure and fiscal deficit are watched keenly by the rating agencies which can influence cost of borrowing for the government and corporates, depending on their rating upgrades or downgrades. They also significantly affect FII flows and consequently the external value of the rupee. More importantly, at the present juncture, we need to reclaim economic goals obscured by, what could be called political nationalism. Budget offers an opportunity to do that.

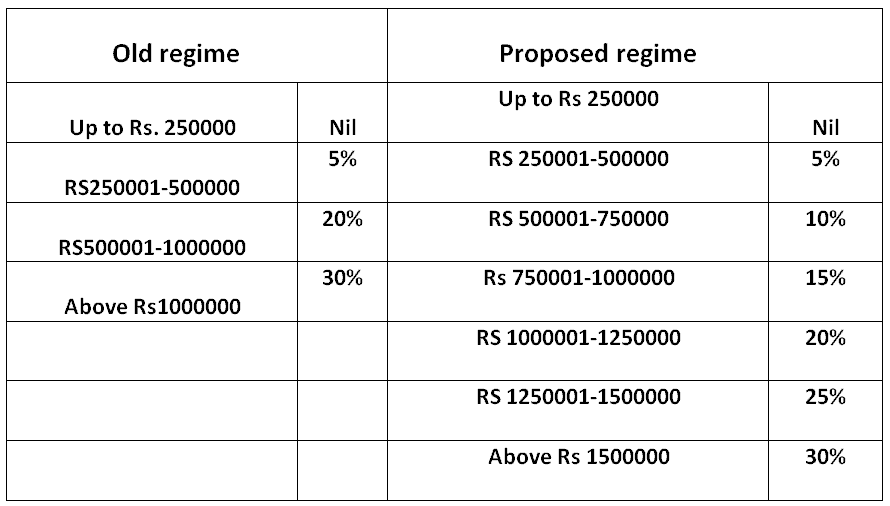

And of course, budgets are eagerly awaited for the tax proposals that affect Aam Aadmi. It is claimed that the latest budget simplifies the tax regime. But against the earlier four slabs for income tax, we now have seven and instead of one universal system of personal taxation we now have a dual system. The concept of “simplification” has become more complex indeed! Well, when self serving bureaucracy meets the blinkered political class, tongue-in-cheek parliamentary parleys could easily lapse into Orwellian double-speak!!

Nevertheless, we ordinary citizens, need to navigate the budget and it must be conceded from the point of view of Aam Aadmi, it could be called a “middle class budget”, that is, for those whose income is in the range of Rs 15 lacs. The budget makes its intention of phasing out the numerous exemptions very clear. To begin with, it has offered the tax payer two options as follows. While under the old regime the tax payer can continue to avail of various tax deductions, under the proposed regime most of these will be eliminated.

TAX SLAB RATES

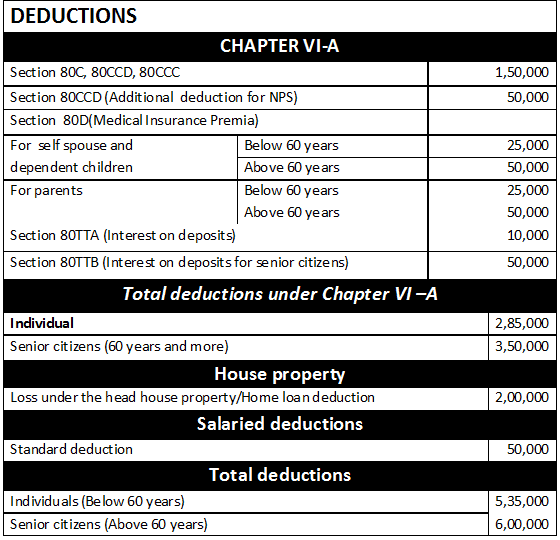

But what are the most availed of deductions which will be forgone under the proposed regime? The same are listed out below. There are of course others, such as HRA, donations to political parties, etc that will also be forgone. And there are deductions that continue even under the proposed regime. For instance, standard deduction of 30% of the income from house property and 80G deductions would still be available.

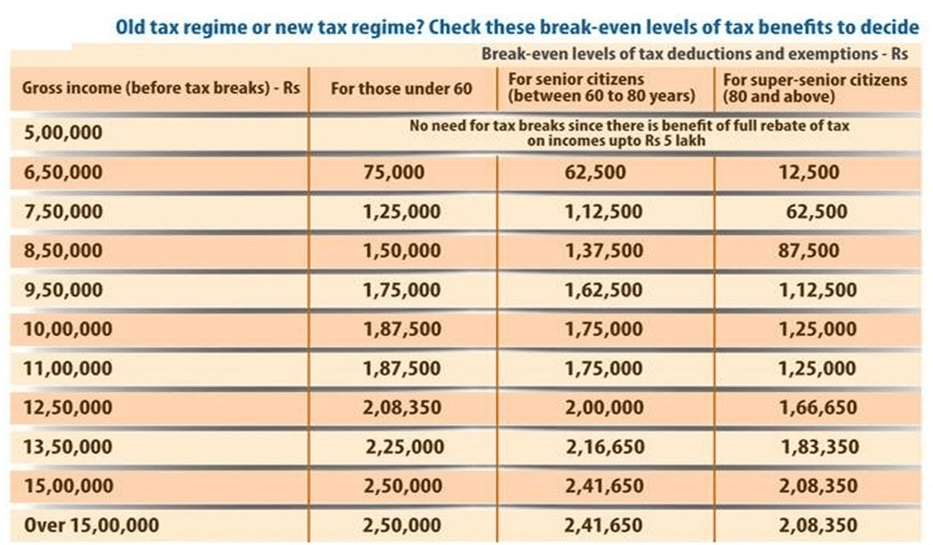

So how does one decide which alternative to opt for? A person who is less than 60 and with an income of Rs 10 lacs a year would end up paying Rs 37500 more tax under the old regime than under the proposed regime, if no deductions are availed of. To offset this extra tax burden she/he would have to take advantage of tax deductions of at least Rs 187500/- which would be the breakeven point to decide which regime she/he should opt for. Thus if the tax payer is in a position to get tax deductions of Rs 187500/- or more at an income level of Rs 10 lacs, remaining under the old regime would be beneficial. We can compute such breakeven points for each level of income and construct a decision matrix to determine which regime to opt for. If the tax deductions and exemptions equal or exceed below mentioned break-even levels, continue with old tax regime, otherwise go for the new regime.

The budget has abolished Dividend Distribution Tax (DDT). But then dividends will be taxed in the hands of the recipients! At present while dividends are tax free in the hands of the recipients, companies are required to deduct around 20.5% of the gross dividend amount before distribution of dividend. So all those whose tax liability is less than 20% suffer an indirect tax incidence of 20% plus, under the DDT dispensation. Hence this measure again will benefit those who fall in the tax bracket of 20% or less. This measure is also likely to benefit NRIs/OCIs whose global income is taxed and are residing in tax jurisdictions with whom India has Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA). This class of investors were deprived of claiming any set off in respect of DDT, against tax payable on their global income in the country of their residence, since DDT was paid by the company but not by them directly. On the other hand, promoters and HNIs are likely to witness substantial increase in their tax liability and quite many of them may have to shell out tax at, what appears like a confiscatory rate of 42%.

One way to avoid DDT is to take exposure to equities through growth schemes of equity mutual funds which are, being “pass through” vehicles, are not taxed on the income earned by them, including dividends on their pool of investments. The only tax incidence the investor has to suffer under equity MF growth schemes, is at the time of redemption and that too at 10% of the gains realized, with a tax free threshold of 1 lac for such gains realized in a financial year. This is true of debt mutual funds as well, where DDT could be as high as 29%. So growth schemes will be better than dividend schemes, even in the case of debt funds where tax rate on gains is 20% without the tax free threshold of 1 lac, but with indexation benefit.

Budget also seeks to tighten the tax net by tweaking the criteria to decide the status of the tax payer as ‘Resident’, Resident but not ordinarily resident (NOR) and Non-Resident (NR). Among other things, the budget has proposed that an Indian citizen who is not liable to pay tax in any other country or territory shall be deemed to be a resident in India. This change could have had the unintended (?) consequence of bringing into the Indian tax net the incomes earned abroad by bona fide NRI workers in countries that did not levy income tax. Thankfully, the Finance Ministry quickly clarified that in case of an Indian citizen who becomes a deemed resident of India under the proposed provision, income earned outside India by such person shall not be taxed in India, unless it is derived from an Indian business or profession. In short, bona fide NRIs working in countries that do not levy income tax need not worry about these incomes being taxed in India. However, one needs to wait for the Finance Act to be passed to understand the details of this provision regarding the “income derived from an Indian business or profession”. At present, income accrued outside India from a business or profession controlled from India is not taxed for non-residents. This could change from FY 21.

One other measure to reassure the retail depositor rattled in the wake of PMC Bank fiasco, Is the increase in the insurance cover for bank deposits to Rs 5 lacs from the prevailing Rs 1lac. However, this limit which is uniform across all banks raises issues of “moral hazard”, as all banks and indirectly their depositors, share the cost of the cover uniformly, although the risks vary widely from PSU to Private to Co-operative banks. But that’s a debate, best left for another day!